Antipyretics for children are prescribed by a pediatrician. But there are emergency situations with fever when the child needs to be given medicine immediately. Then the parents take responsibility and use antipyretic drugs. What is allowed to be given to infants? How can you lower the temperature in older children? What medications are the safest?

Ordin-Nashchokin Afanasy Lavrentievich - diplomat, boyar, governor. He directed foreign policy in 1667-1671, Ambassadorial and other orders. He signed a treaty of alliance with Courland (1656), the Treaty of Valiesar (1658), and concluded the Truce of Andrusovo with the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (1667). In 1671 he retired. In 1672 he became a monk. Ordin-Nashchokin was presumably born in 1605 into a nobleman’s family in the Pskov suburb of Opochka. From early childhood he loved to read and showed a passion for science. He learned to read from a local priest, and Afanasy was taught languages - Latin and Polish - by a Pole who served with the Nashchokins. As soon as Afanasy was 15 years old, his father took him to Pskov to enlist in the regiment to serve the sovereign. Educated, well-read, fluent in several languages, well-mannered Ordin-Nashchokin climbed the career ladder thanks to his own qualities: talent and hard work. In the early 1640s, the Ordin-Nashchokin family moved to Moscow.

In 1642, Afanasy was sent to the Swedish border “to clear the lands captured by the Russian Swedes and hay fields along the Meusitz and Pizhva rivers.” The Border Commission was able to return the disputed lands to Russia. At the same time, Ordin-Nashchokin took an active part in this matter: he conducted a survey of local residents, carefully read the interrogations of the “search people,” used scribal and census books, etc. By this time, Russian-Turkish, and therefore Russian-Crimean, conflicts had escalated relationship. It was important for the Moscow government to know whether there were Polish-Turkish agreements on joint actions against Russia. Such an important task was entrusted to Ordin-Nashchokin. On October 24, 1642, he left Moscow with three assistants for the capital of Moldavia, Iasi. The Moldavian ruler Vasile Lupu cordially received the envoy of the Russian Tsar, thanked him for the gifts and promised to help. Afanasy, as a representative of the Moscow state, was provided with quarters, food, and national clothing. Ordin-Nashchokin did not sit idle: he collected information about the plans of the Polish and Turkish governments and their military preparations, and also monitored the situation on the border. He did not lose sight of the actions of Polish residents in Bakhchisaray and Istanbul. Through trusted persons, Ordin-Nashchokin knew, for example, what was discussed at the Polish Sejm in June 1642, about the contradictions within the Polish-Lithuanian government on the issue of relations with Russia. He also observed what the Crimean Khan was doing and reported to Moscow. Ordin-Nashchokin’s mission was of great importance for greater rapprochement between Moldova and Russia. Ordin-Nashchokin’s observations contributed to the conclusion of a peace treaty between Russia and Turkey. This agreement prevented the threat from the south from the Crimeans to Russia.

In 1644, Ordin-Nashchokin was tasked with clarifying the situation in the west, in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, in particular, checking rumors about an allegedly impending Polish-Danish invasion of Russia. Ordin found out that internal unrest in Poland and Lithuania would not allow Vladislav IV to settle border scores with Russia. And Denmark, which was fighting with Sweden, according to the diplomat, did not intend to quarrel with Russia. After the death of Mikhail Fedorovich in 1645, the throne was taken by his son Alexei. B.I. came to power. Morozov, the Tsar's brother-in-law, who replaced F.I. Sheremetev, who patronized Ordin-Nashchokin. Afanasy returned to his family estate, where he was caught in the rebellion of 1650. Afanasy Lavrentievich proposed to the government a plan to suppress the rebellion, which subsequently allowed him to return to service. Ordin-Nashchokin was twice included in the border boundary commissions. In the spring of 1651, he went “to the Meusitz River between the Pskov district and the Livonian lands.” In the mid-1650s, Ordin-Nashchokin became the governor of Druya, a small town in the Polotsk Voivodeship, which adjoined the Swedish lands. Negotiations between the governor and the enemy ended with the withdrawal of Swedish troops from the Druya area. He also negotiated with the residents of Riga about transferring to Russian citizenship. He organized reconnaissance, outlined the paths for the advancement of Russian troops, and convinced the residents of Lithuania of the need for a joint fight against the Swedes.

In the summer of 1656, in Mitau, Ordin-Nashchokin enlisted the support of Duke Jacob, and on September 9, Russia concluded a treaty of friendship and alliance with Courland. Afanasy Lavrentievich corresponded with the Courland ruler, the French agent in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the Polish colonel, and received the Austrian ambassador Augustin Mayerberg, who was heading to Moscow. For such successes, Tsar Alexei appointed him governor of Koknese, subjugating to him the entire conquered part of Livonia. He also received command of all the Baltic cities occupied by Russian troops. Ordin-Nashchokin sought to establish good relations towards Russia among Latvians. He returned unjustly seized property to the population, preserved city self-government on the model of Magdeburg law, and in every possible way supported the townspeople, mainly merchants and artisans. But Ordin-Nashchokin was and remained, first of all, a diplomat, and all his reforms were of a diplomatic nature. Afanasy Lavrentievich believed that the Moscow state needed “marinas” in the Baltic. To achieve this goal, he sought to create a coalition against Sweden and take Livonia from it. He tried to make a deal with Turkey and Crimea and insisted on “making peace with Poland in moderation” (on moderate terms). Ordin-Nashchokin even dreamed of an alliance with the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, of “the glory that would cover the Slavic peoples if they all united under the leadership of Russia and Poland.” However, the foreign policy program of the “Russian Richelieu,” as the Swedes called him, did not meet with understanding from the tsar, despite the great trust and favor that he constantly placed in his minister. In April 1658, Ordin-Nashchokin received the title of Duma nobleman. The king said: “You take care of our affairs with courage and bravery and are kind to the military people, but you don’t let thieves down and stand with our people against the Swedish king of glorious cities with a brave heart.”

At the end of 1658, the Duma nobleman, the Livonian governor Ordin-Nashchokin (being a member of the Russian embassy) was sent by the tsar to secret negotiations with the Swedes: “Take all sorts of measures so that the Swedes speak in our direction in Kantsy (Nienschanz) and near Rugodiv (Narva) ship piers and from those piers for travel to Korela on the Neva River the city of Oreshek, and on the Dvina River the city of Kukuinos, which is now Tsarevichev-Dmitriev, and other places that are decent.” He had to tell the Order of Secret Affairs about the results of the negotiations. The ambassadorial congress began in November near Narva in the village of Valiesare. The Emperor was in a hurry to conclude the agreement, sending more and more instructions. In accordance with them, Russian ambassadors demanded the concession of the conquered Livonian cities, Korel and Izhora lands. The Swedes sought to return to the terms of the Stolbovo Treaty. The truce signed on December 20, 1658 in Valiesar (for a period of 3 years), which actually provided Russia with access to the Baltic Sea, was a major success of Russian diplomacy. Russia retained the territories it occupied (until May 21, 1658) in the Eastern Baltic. Free trade was also restored between both countries, travel, freedom of religion, etc. were guaranteed. Since both sides were at war with Poland, they mutually decided not to use this circumstance. The Swedes agreed with the honorary title of the Russian Tsar. And most importantly: “There will be no war and fervor on both sides, but peace and quiet.” However, after the death of King Charles X, Sweden abandoned the idea of “eternal peace” with Russia and even made peace with Poland in 1660. Russia once again faced the possibility of fighting a war on two fronts. Under such circumstances, Moscow sought to conclude an agreement with Sweden in order to transfer all its forces to the southern side. In this situation, Ordin-Nashchokin, in letters to the tsar, asks to be released from participation in negotiations with the Swedes. On June 21 in Kardis, boyar Prince I.S. Prozorovsky signed a peace agreement: Russia ceded to Sweden everything it had won in Livonia. At the same time, freedom of trade for Russian merchants and the liquidation of their pre-war debts were proclaimed. Ordin-Nashchokin’s participation in the Russian-Polish negotiations of the early 1660s, which became an important stage in the preparation of the Andrusovo Agreement, was exceptionally active. Realizing how difficult it would be to achieve reconciliation with the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, he solved this problem gradually. In March - April, an exchange of prisoners took place, and in May an agreement was reached on the security of the ambassadors. But in June, a conflict emerged in the incompatibility of the parties’ positions on issues of borders, prisoners, and indemnity. Great restraint was required from the Russian ambassador so as not to interrupt the negotiations.

Between September and November 1666, Polish diplomats tried to return Lithuania, Belarus and Ukraine and, having encountered refusal, threatened to continue the war. In a report to Moscow, Ordin-Nashchokin advised the Tsar to accept Polish conditions. In the last days of December, on behalf of the Tsar, Dinaburg was ceded to the Poles, but the ambassadors insisted on recognizing Kyiv, Zaporozhye and the entire Left Bank Ukraine as Russia. By the end of the year, the foreign policy position of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth had changed, and Polish representatives became more compliant. Already being a okolnichy, Ordin-Nashchokin soon took an active part in the renewed Russian-Polish negotiations. His restraint, composure, and diplomatic wisdom largely predetermined the signing of the most important agreement on January 30 (February 9), 1667 - the Peace of Andrusovo, which summed up the long Russian-Polish war. A truce was established for 13.5 years. Other important issues of bilateral relations were also resolved, in particular, joint actions against Crimean-Ottoman attacks were envisaged. On the initiative of Ordin-Nashchokin, Russian diplomats were sent to many countries (England, Brandenburg, Holland, Denmark, the Empire, Spain, Persia, Turkey, France, Sweden and Crimea) with “declaratory letters” on the conclusion of the Andrusovo truce, an offer of friendship, cooperation and trade. “The glory of the thirty-year truce that thundered in Europe, which all Christian powers desired,” wrote a contemporary of the diplomat, “will erect the noblest monument to Nashchokin in the hearts of his descendants.” The negotiations preparing the Andrusovo Peace took place in several rounds. And Ordin’s return to Moscow during one of the breaks (1664) coincided with the trial of Patriarch Nikon and his supporter, boyar N.I. Zyuzin, whom Ordin treated with sympathy. This cast a shadow on the Duma nobleman, although his complicity with Nikon was not proven. Nevertheless, Afanasy Lavrentievich had to ask the Tsar for forgiveness. Only the trust of Alexei Mikhailovich, as well as the selflessness and honesty of Ordin-Nashchokin himself, saved him from dire consequences: he was only removed to Pskov by the governor. But even in this position, Ordin remained a diplomat. He negotiated and corresponded with Lithuanian and Polish magnates, and thought about the delimitation of lands bordering Sweden. And to advance the cause of peace with the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, he tried to involve the rulers of Austria and Brandenburg, Denmark and Courland in mediation. Being an educated man, Ordin tried to give his son a good education. Warrior Afanasyevich “was known as an intelligent, efficient young man,” even sometimes replacing his father in Koknes (Tsarevich-Dmitriev city). But “passion for foreigners, dislike for his own” led him to flee abroad. True, in 1665 he returned from abroad and was allowed to live in his father’s village. However, this did not harm Ordin-Nashchokin’s career.

In February 1667, Ordin-Nashchokin received the titles of close boyar and butler and was soon appointed to the Ambassadorial Prikaz with the rank of “Royal and State Ambassadorial Affairs of the Boyar.” In the same year, Afanasy Lavrentievich invented a new seal, and the tsar also entrusted him with the Smolensk rank, the Little Russian order, as a result of which the main departments of the state were in the hands of Ordin-Nashchokin. Ordin-Nashchokin worked hard to expand and strengthen his country’s ties with other states. Thus, the Russian diplomat repeatedly made attempts to establish diplomatic missions abroad. So, in July 1668, Vasily Tyapkin was sent to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth “to be a resident there forever.” But in order to expand the country’s ties with other states, it was necessary to be aware of what was happening in these states. Therefore, Afanasy established a postal connection with Vilna and Riga; the next step he proposed was to translate foreign newspapers and compile reports from them. These reports became the prototype of printed newspapers that would appear later. During the leadership of the Ambassadorial Prikaz (from February 1667 to February 1671), Ordin-Nashchokin regulated the activities of this department. The personnel composition has increased significantly due to highly professionally trained employees, because “it is necessary to direct mental attention to state affairs to the blameless and chosen people.” Afanasy Lavrentievich considered the Ambassadorial Prikaz to be one of the most important government departments, “it is the eye of all great Russia, both for the state’s highest honor, together with health, and having providence on all sides and relentless care from the fear of God.” Ordin-Nashchokin was well prepared for the diplomatic service: he knew how to write “adjunctive”, knew mathematics, Latin and German, and was knowledgeable in foreign practices; They said about him that he “knows German business and knows German customs.” He was not against borrowing knowledge from abroad; he believed that “a good man is not ashamed to learn from the outside, even from his enemies.” For all his dexterity, Ordin-Nashchokin possessed one diplomatic quality that many of his rivals did not have - honesty. Despite the fact that the profession of a diplomat requires such a quality as cunning, which Ordin-Nashchokin undoubtedly possessed, he was, moreover, a man of honor. Even by cunning, he tried not to violate the agreement concluded in any way. His personal qualities also included hard work, initiative, and resourcefulness, but it was difficult for him to yield to the king and his entourage in matters of state, which is why Afanasy was not afraid to openly enter into conflicts and defend his opinion. The tsar loved and appreciated him very much; Ordin-Nashchokin enjoyed the tsar’s boundless trust. I was offended that they did not send the necessary papers; they called me to Moscow without explaining the reasons. So, Ordin-Nashchokin was in an aura of glory and enjoyed the unlimited trust of the tsar. But the tsar began to be irritated by too independent actions and independent decisions, as well as Ordin-Nashchokin’s constant complaints about the lack of recognition of his merits. The head of the Ambassadorial Prikaz had to explain himself. Later, the tsar discovered that Afanasy's work as head of the Little Russian Prikaz was not successful, and removed Ordin-Nashchokin from this position.

In the spring of 1671, the title of “guardian” was deprived. In December, the tsar accepted the resignation of Ordin-Nashchokin and “clearly freed him from all worldly vanities.” At the beginning of 1672, Afanasy Lavrentievich left Moscow and took with him a huge personal archive, consisting of ambassadorial books, royal letters, but all this was returned to the capital after his death. In the Krypetsky Monastery, 60 kilometers from Pskov, he became a monk, taking the name of the monk Anthony. A few years later, Monk Anthony returned to Moscow to present his foreign policy views to Tsar Fyodor Alekseevich, but his ideas were of no importance, because during his stay in the monastery he “lagged behind” the real situation in the political field. At the end of 1679 he returned to Pskov, and a year later he met death in the Krypetsky Monastery. Foreign diplomats suffered from Ordin-Nashchokin’s cunning. “He was a master of original and unexpected political constructions,” says the great Russian historian Klyuchevsky about him. “It was difficult to argue with him. Thoughtful and resourceful, he sometimes infuriated the foreign diplomats with whom he negotiated, and they blamed him for the difficulty to deal with him: he will not miss the slightest mistake, no inconsistency in diplomatic dialectics, he will now pry and confuse a careless or short-sighted enemy."

Afanasy Lavrentievich Ordin-Nashchokin - Moscow statesman of the 17th century

Among the 109 figures in the high relief of the “Millennium of Russia” monument in Novgorod, symbolizing the history of our state, there is also the figure of Opochanin Afanasy Lavrentievich Ordin-Nashchokin. There was no such outstanding political figure and diplomat of this magnitude in Russia either in the pre-Petrine era or under Peter I. No wonder foreigners called Ordin-Nashchokin “Russian Richelieu.” Fragment of the high relief of the monument “Millennium of Russia”

Alexander Lavrentievich was born into the family of a poor Pskov nobleman around 1606. He descended from a certain “Nashchoka” - a participant in the uprising of the inhabitants of Tver against the Khan’s bas-kak Chol Khan, wounded in the cheek in 1327. He spent his childhood and adolescence in the Pskov region - in Opochka . Local sextons taught him literacy and mathematics, the Poles taught him Polish and Latin, and later he himself mastered German and Moldavian, as well as the contemporary Russian literary language, rhetoric - as he himself put it, he learned to “write syllabically.” In December 1621, when Afanasy was supposedly 15 years old, his father took him to Pskov and enrolled him in the Pskov regiment for the sovereign's service as the son of a boyar (the lowest rank of serviceman in the fatherland) from Opochka. Ordin-Nashchokin's childhood

Pskov Uprising of 1650 At first, an educated person who knew “German morals” began to be given diplomatic assignments, including participation in border congresses and an embassy to Moldova. Ordin-Nashchokin became known to Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich only in 1650, when Afanasy Lavrentievich played a major role in suppressing the Pskov uprising.

In the difficult war with Poland of 1654-67, Ordin-Nashchokin commanded a detachment or regiment; was the governor of the cities of Drui and Kokenhausen in Livonia. In 1658, Ordin-Nashchokin signed the beneficial Valiersar Truce with Sweden; negotiated with Courland and Poland, sought an alliance with the latter for a successful struggle with Turkey and Sweden for access to the sea.

In 1667, under the editorship of Ordin-Nashchokin, the New Trade Charter was drawn up. From the point of view of economic policy, the charter is a monument to the policy of mercantilism. According to its content, it can be divided into two parts: - general issues of organizing customs administration, problems of Russian trade; - rules governing the trade of foreigners. The ambassadorial order, in which the New Trade Charter was drawn up. The New Trade Charter was needed to create conditions for the development of exports, limiting imports and increasing the state treasury, as well as to create economic independence of Russia from the commercial capital of foreign countries

The Truce of Andrusovo is an agreement concluded in 1667 between Russia and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth for 13.5 years. The name comes from the village of Andrusovo (now Smolensk region), in which it was signed. The truce ended the war that had lasted since 1654 over the territories of modern Ukraine and Belarus. Russia managed to return the lands that belonged to it before the Time of Troubles. It also led to a rapprochement between Russia and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth on the basis of a joint struggle against the Ottoman Empire.

"Eagle" - the first Russian double-decker warship - was built in 1669. The shipyard was founded in the village of Dedinovo, 26 km from Kolomna. This place on the left bank of the Oka at the confluence of the Moscow River became the first Russian admiralty. The organizer of the construction was A.L. Ordin-Nashchokin. Ship "Eagle"

Ordin-Nashchokin is credited with organizing the first post offices in Russia (1669).

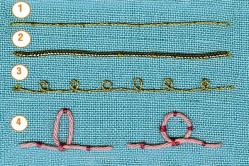

At the time when A.L. Ordin-Nashchokin was in charge of the Ambassadorial Prikaz, he used a special secret script, the key of which is shown in the figure. Secret writings were used to write “in memory”, that is, instructions to the clerks of the Order of Secret Affairs, who traveled abroad on various, sometimes very important, assignments.

End of career and death All achievements in the service aroused the hatred of the noble boyars towards the “artistic” nobleman. Disagreements with the tsar led to the resignation of Ordin-Nashchokin. In 1671, he took monastic vows at the Krypetsky Monastery near Pskov, where he died in 1680 as the monk Anthony.

Ordin-Nashchokin was a diplomat of the first magnitude - “the most cunning fox,” in the words of foreigners who suffered from his art. “He was a master of original and unexpected political constructions,” says the great Russian historian Klyuchevsky about him. “It was difficult to argue with him. Thoughtful and resourceful, he sometimes infuriated the foreign diplomats with whom he negotiated, and they blamed him for the difficulty to deal with him: he will not miss the slightest mistake, no inconsistency in diplomatic dialectics, he will now pry and confuse a careless or short-sighted enemy."

Ordin-Nashchokin - Western politician The Russian chancellor was involved in many other things - iron factories, manufactories, trading yards and so on. He strove to bring the country out of backwardness, firmly defended state interests, without fear of disgrace; He was constantly active and completely incorruptible, and fought against the clerical routine. Nashchokin was one of the few Westerners who thought about what could and should not be borrowed, who sought an agreement between pan-European culture and national identity.

Being the Pskov governor in 1665, he carried out a reform with the introduction of elements of self-government, and tried to create the first bank in Russia.

Afanasy Lavrentievich Ordin-Nashchokin

Ordin-Nashchokin Afanasy Lavrentievich (in monastic life - Anthony ) (1605-1680), major statesman of the 17th century, diplomat. He came from Pskov nobles.

In childhood and adolescence, Ordin-Nashchokin received a good education. From 1622 he was in military service. During the Russian-Swedish War of 1656 - 1661, Ordin-Nashchokin commanded large formations of troops and led the assault on the city of Drissa. Beginning in the 1640s, he was actively involved in diplomatic activities. In 1656 he signed an alliance treaty with Courland, and in 1658 - the Velisar truce with Sweden, for which he received the rank Duma nobleman. In 1667, Ordin-Nashchokin obtained from Poland the signing of the Truce of Andrusovo, which was beneficial for Russia. After this, he received the rank of boyar and began to head the Ambassadorial order. Ordin-Nashchokin proposed expanding economic and cultural ties with the countries of Western Europe and the East, concluding an alliance with Poland for a joint struggle with Sweden for possession of the Baltic Sea coast.

He was a supporter of a number of important reforms. He proposed reducing the noble militia, increasing the number of rifle regiments, and also introducing a recruiting system for recruiting troops in Russia. He was one of the creators of the New Trade Charter (1667), which abolished the privileges of foreign companies and provided benefits and advantages to Russian merchants. According to the Ordin-Nashchokin project, postal communication was established between Moscow, Vilna and Riga, and “Chimes” began to be regularly published - handwritten newspapers in one copy containing information about events taking place in foreign countries. Ordin-Nashchokin proposed limiting power governor locally, establish city self-government, create a special “Merchant Order”. He founded a number of manufactories in Russia.

In 1672 he became a monk.

O.M. Rapov

Ordin-Nashchokin Afanasy Lavrentievich (c. 1605-1680) - Russian statesman and military leader and diplomat of the 2nd half of the 17th century. Since 1658 - Duma nobleman, since 1665 - okolnichy, since 1667 - boyar. Born into the family of a Pskov nobleman, he grew up in Opochka and received a good education (he studied foreign languages, mathematics, and rhetoric). From 1622 he was in “regimental service” in Pskov, and from the 40s he was involved in the diplomatic service. In 1650, he tried to prevent an uprising in Pskov, and when it began, he fled, fearing the wrath of the rebels, to Moscow and actively contributed to its suppression. During the Russian-Polish and Russian-Swedish wars, Ordin-Nashchokin took part in the assault on Vitebsk (1654), a campaign against Dinaburg, led the assault on Drissa (1655), carried out a raid near Dynamünde and Riga. In 1656 he signed a treaty of friendship and alliance with Courland and began relations with Brandenburg. In 1658, he negotiated with the Swedes, which ended with the signing of a truce (see Treaty of Valiesar, 1658). In 1662-1666 he participated in negotiations with Poland and signed the Truce of Andrusovo in 1667. In 1665, Ordin-Nashchokin was the governor of Pskov, and in 1667 he was appointed head of the Ambassadorial Prikaz. In 1671 he was dismissed from service, and in 1672 he took monastic vows (under the name Anthony) at the Krypetsky Monastery in Pskov. In 1679 he took part in negotiations with the Poles. For his service, Ordin-Nashchokin was granted rich estates and estates (Poretsk volost of Smolensk district, 500 peasant households in Kostroma district, etc.) and in the 60s he became a large feudal landowner.

Ordin-Nashchokin, especially during the period of leadership of the Ambassadorial Prikaz, significantly intensified Russia's foreign policy. He was a supporter of an alliance with Poland to fight Sweden for access to the Baltic Sea and repel Turkish aggression. Under the Valiesar Truce, he achieved the retention of the Estonian and Livonian cities captured by Russian troops for a period of 3 years. Ordin-Nashchokin considered it necessary to make peace with Poland and continued the war for Livonia with Sweden. When negotiating with the Poles, he advised the tsar to present moderate demands to them that would not undermine the basis for concluding a future alliance between Russia and Poland.

Ordin-Nashchokin was a supporter of the progressive transformation of Russia in the field of military. and economic, supported the development of trade and industry. In the 50s, he proposed reforming the army by introducing recruitment, increasing the streltsy army and reducing the ineffective noble cavalry. Being a governor in Druya and Koknese (Kokenhausen) in 1655-1656, Ordin-Nashchokin strove for the economic revival of the Podvina region, encouraged trade and created a shipyard on the Western Dvina. In 1665, he drew up a project for city government in Pskov and transferred a significant part of his functions as a governor to elected representatives from among the “best” people of the settlement. He supervised the drafting of the New Trade Charter of 1667. Ordin-Nashchokin supervised the activities of P. Marcelis' factories and supervised the construction of a shipyard on the Oka River in the village of Dedinovo. He was the initiator of the establishment of mail between Moscow, Riga and Vilnius, as well as the regular compilation of the handwritten newspaper “Chimes”.

E. V. Chistyakova. Moscow.

Soviet historical encyclopedia. In 16 volumes. - M.: Soviet Encyclopedia. 1973-1982. Volume 10. NAHIMSON - PERGAMUS. 1967.

Literature: Ikonnikov V.S., Near Boyar A.L. Ordin-Nashchokin, "PC" 1883, vol. 40, No. 10-11; Klyuchevsky V. O., A. L. Ordin-Nashchokin. Moscow statesman of the 17th century, "Scientific Word", 1904, c. 3; Chistyakova E.V., Socio-economic views of A.L. Ordin-Nashchokin, "Proceedings of the Voronezh State University", 1950, vol. 20; Galaktionov I., Chistyakova E., A. L. Ordin-Nashchokin, rus. diplomat of the 17th century, M., 1961; Kopreeva T.N., Unknown note by A.L. Ordin-Nashchokin about Russian-Polish relations, 2nd half. XVII century, "PI", vol. 9, M., 1961.

Ordin-Nashchokin, Afanasy Lavrentievich (d. 1680) - an outstanding Russian diplomat. The son of a poor Pskov landowner, Ordin-Nashchokin received a fairly good education for his time, studied mathematics, foreign languages (Latin and German), and became familiar with the procedures in foreign countries. Ordin-Nashchokin’s theoretical training and personal talent attracted the attention of the Russian government to him. Back in 1642, he was entrusted with carrying out border delimitation with Sweden.

Ordin-Nashchokin especially distinguished himself as a diplomat during the Russian-Swedish war of 1656-1658. After the capture of Kukonois by Russian troops, Ordin-Nashchokin was appointed to the voivodeship there and became the de facto ruler of Livonia. Ordin-Nashchokin was a supporter of the anti-Swedish foreign policy program, considering it necessary for the Russian state to establish itself on the shores of the Baltic Sea and acquire sea harbors. The time Ordin-Nashchokin was in Livonia was a convenient moment for realizing this goal, since a coalition was formed against Sweden from the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the German Empire, Denmark and Brandenburg. Understanding the impossibility of a simultaneous war with Sweden for Livonia and with Poland for Ukraine, Ordin-Nashchokin spoke out for peaceful relations with Poland and was even ready to sacrifice Ukraine. In an effort to strengthen Russian positions against Sweden, Ordin-Nashchokin achieved the official transfer of Courland under the patronage of Russia. In order to counter the Swedish fleet, Ordin-Nashchokin took measures to build a Russian fleet on the Western Dvina. However, Ordin-Nashchokin’s plans did not receive support in Moscow. In the foreign policy of the Russian state, the line of supporters of the war with Poland, supported by Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich, won. It was decided to begin peace negotiations with Sweden, the conduct of which was entrusted to Ordin-Nashchokin. As a result of negotiations in December 1658, a truce was concluded in Valiesar for 3 years, according to which Russia maintained its conquests in Livonia.

The Treaty of Kardis in 1661 returned Sweden to its possessions in Livonia, assigned to Russia under the Truce of Valiesar. Thus, Ordin-Nashchokin’s diplomatic plans were destroyed. But, despite this, he continued to stubbornly seek the implementation of his program before the tsar, offering to make peace with Poland and proving that the possession of Livonia was more profitable than the annexation of Ukraine.

In 1662, Ordin-Nashchokin traveled as part of the Russian embassy for peace negotiations in Poland; negotiations, however, did not take place. In 1664, he was appointed one of the delegates to the Russian-Polish ambassadorial congresses near Smolensk. Before leaving, Ordin-Nashchokin presented a memo to the Tsar, insisting on an alliance with Poland in order to turn the joint forces of both states against Sweden. Ordin-Nashchokin drew in his note the prospect of uniting the Slavic peoples under the leadership of Russia and Poland. The ambassadorial congresses of 1664 did not produce results.

In 1666, Ordin-Nashchokin was again sent to Smolensk to participate in new congresses with Polish representatives, now as a “great and plenipotentiary ambassador.” The congresses began in May 1666 in Andrusovo, near Smolensk. In January 1657, Ordin-Nashchokin concluded the Treaty of Andrusovo (...), which marked the great diplomatic success of the Russian state.

Upon his return from Andrusovo, Ordin-Nashchokin was granted a boyar status, and then appointed head of the Ambassadorial Prikaz with the title of “royal great seals and guardian of state great embassy affairs.” Ordin-Nashchokin highly regarded the tasks of the Ambassadorial Prikaz, considering it “the eye of all great Russia.” According to Ordin-Nashchokin, the Ambassadorial Prikaz was supposed to have “providence” and “persistent care” for the state good. Ordin-Nashchokin made every effort to improve the quality of diplomatic personnel. He emphasized that the Ambassadorial Order should be “guarded like the apple of his eye... by blameless people.” They must have experience, initiative, independence and strive to place the diplomatic service at a high level. The quality of the diplomatic service, from Ordin-Nashchokin’s point of view, was determined not by the number of embassy workers, but by their talents and sense of responsibility for their work. Being an opponent of the unconditional borrowing of foreign experience, Ordin-Nashchokin at the same time adhered to the rule that “a good person is not ashamed to learn from the outside, from strangers, even from his enemies.” In order to keep the Ambassadorial Prikaz informed of foreign events, the translators of the Ambassadorial Prikaz compiled so-called “chimes”, i.e., handwritten summaries of foreign news, based on foreign newspapers and reports coming from abroad. The ambassadorial order was thus aware of what was happening in Western European countries. Ordin-Nashchokin took the initiative to create a diplomatic post between Russia and Poland.

As the head of the Ambassadorial Prikaz and the head of the foreign policy of the Russian state, Ordin-Nashchokin took measures to ensure Russia’s trade interests in relations with countries of the West and East. The New Trade Charter of 1667, also associated with the name of Ordin-Nashchokin, based on mercantilistic principles, regulated the trade of foreigners in order to eliminate competition in the Russian market. Under Ordin-Nashchokin, a number of embassies to the West were equipped for diplomatic and trade purposes: to Spain, France, Venice, Holland, England, Prussia, Sweden. In May 1667, Ordin-Nashchokin concluded a trade agreement with the Armenian “Persian Company”, which traded in silk. He also took care of strengthening trade ties with Bukhara and Khiva, and equipped an embassy to India.

The main problem of the foreign policy of the Russian state when Ordin-Nashchokin was head of the Ambassadorial Prikaz was the Ukrainian question. Ordin-Nashchokin participated in congresses with Polish delegates in 1669-1670. At this time, political differences emerged between Ordin-Nashchokin and the tsar. Ordin-Nashchokin stood for compliance with the terms of the Andrusov Treaty, while opponents of Ordin-Nashchokin’s foreign policy line sought not only to retain Kyiv for Russia after the two-year period agreed upon by the truce, but also to annex Right Bank Ukraine. This direction was supported by the king himself. Peaceful relations with the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth seemed necessary to Ordin-Nashchokin in order to resolve a more important, from his point of view, foreign policy task - the annexation of the Baltic Sea coast.

Dissatisfaction in government circles with the actions of Ordin-Nashchokin soon led to his removal, first from the post of head of the Little Russian Prikas, and then the Ambassadorial Prikaz. At the beginning of 1671 the question arose about sending an embassy to Poland to conclude peace. Ordin-Nashchokin was appointed ambassador plenipotentiary, but at the same time he was removed from the management of the Ambassadorial Prikaz and deprived of the title of “guardian”. Ordin-Nashchokin’s place was taken by his political opponent A.S. Matveev (...), who was entrusted with preparing the ambassadorial order for Ordin-Nashchokin. The order deprived the ambassador of freedom of “industry” (initiative) and asked him to act within strictly limited limits, in the role of a simple executor of received instructions. Ordin-Nashchokin stated that under such conditions “it was impossible for him to be in that embassy service,” and, under the pretext of illness, he refused to participate in the embassy. After this he retired to a monastery. Nevertheless, in 1679 he successfully participated in negotiations on the extension of the Andrusovo truce.

Ordin-Nashchokin was a diplomat of great intelligence and talent, with good theoretical and practical training.

His most characteristic feature was the desire for independence in carrying out his foreign policy program: “you cannot wait for the sovereign’s decree for everything.” This is where his conflicts with the king arose. As a diplomat, he was distinguished by great skill in negotiations and at the same time great integrity.

Diplomatic Dictionary. Ch. ed. A. Ya. Vyshinsky and S. A. Lozovsky. M., 1948.

Ordin-Nashchokin Afanasy Lavrentievich (c. 1605–1680), economist who laid the foundation for political economy in Russia, statesman and military leader, diplomat Ser. and 2nd floor. XVII century Born into the family of a Pskov nobleman, he received a good education (he spoke Latin, German, Polish, French, Moldavian and other languages, studied mathematics and rhetoric). From 1622 he was on “regimental service” in Pskov, and from the 40s on diplomatic service. In 1658, for the successful conclusion of the Valiesar truce with the Swedes, he was promoted to Duma nobleman. In n. In the 60s, Ordin-Nashchokin, as the Pskov governor, carried out a reform that helped strengthen the rights of merchants and artisans. After being recalled from Pskov to negotiate with the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, in 1667 he concluded the Truce of Andrusovo, which was beneficial for Russia, for which he received the boyar rank and was appointed head of the Ambassadorial Prikaz and head of other institutions. In the same year, under the editorship of Ordin-Nashchokin, the New Trade Charter was drawn up, which determined the main directions of the foreign trade policy of the Russian state.

General issues of organizing customs administration, problems of Russian trade;

Rules governing the trade of foreigners.

The customs tariff of the New Trade Charter bore strong features of protectionism. The increase in duties was achieved by forcing a low exchange rate of gold and efimkas, with which Western merchants had to pay duties. At the same time, the Russian state treasury received approx. 30% net profit. Trade of foreigners within Russia was taxed at more than four times the level of trade of Russian merchants. While protecting the all-Russian market from being captured by foreign trading capital, the duty system was supposed to contribute to the overall economic results of foreign trade - to ensure a positive trade balance and increase the influx of precious metals into the country.

In accordance with the New Trade Charter, a special economic duty was introduced on goods the import of which Ordin-Nashchokin considered necessary to limit. At the same time, measures were taken to expand the export of Russian goods. The New Trade Charter provided for restrictions on the import of luxury goods and a high duty on imported wine.

The role of the New Trade Charter is to create conditions for the development of exports, limiting imports and increasing the state treasury.

The compiler of the New Trade Charter fought for the economic independence of Russia from the commercial capital of foreign countries.

In 1671, Ordin-Nashchokin was dismissed from service and soon (1672) became a monk (under the name Anthony) in the Krypetsky monastery near Pskov. In 1679 he was again involved in diplomatic activities and participated in negotiations with the Poles. Ordin-Nashchokin did not leave any special economic works, but his statements on various political and economic issues, set out in letters and reports to the tsar, and all his government activities indicate that he was an outstanding politician and economist.

Ordin-Nashchokin’s economic views are the first manifestation of Russian mercantilism. Being a spokesman for the interests of the merchants, he paid a lot of attention to issues of trade and its organization. At the same time, Ordin-Nashchokin, in all his state activities, proceeded from the fact that the country’s national economy represents a single whole; this distinguished him from many of his predecessors, who focused their attention on the development of individual sectors of the economy.

Ordin-Nashchokin considered trade a tool for the development of productive forces and the main source of replenishment of the treasury. He advocated the development of “free”, duty-free trade within the country and the expansion of foreign trade. The documents developed by Ordin-Nashchokin implied strict regulation of foreign and domestic trade. He advocated the establishment of a state monopoly of foreign trade on a number of goods, and sought to eliminate two main obstacles from the development of domestic trade - the privileges of foreign merchants and the arbitrariness of governors. To strengthen the position of the Russian merchants in the competition with foreigners, Ordin-Nashchokin proposed organizing merchant partnerships that would prevent foreign merchants from buying Russian goods at low prices. Russian mercantilism of Ordin-Nashchokin had special features. Unlike Western mercantilists, he viewed the development of industry not only as a tool for obtaining money and a means of increasing exports, but also as a means of satisfying the needs of the country's population for necessary goods. Ordin-Nashchokin sought to strengthen the independence and economic power of the state, for which he tried to develop not only trade, but also domestic industry, and fought to strengthen monetary circulation in the country. Ordin-Nashchokin saw the source of wealth in the development of industry.

He took an active part in the organization of metallurgical and metalworking enterprises, leather, paper and glass factories. Ordin-Nashchokin was a supporter of private initiative and free enterprise of both Russian merchants and foreign industrialists. He considered the main obstacle to the development of industry to be the restriction of initiative and lack of assistance from the state. Ordin-Nashchokin objectively assessed the achievements of more developed countries and called for borrowing the best practices of Western countries. At his insistence, specialists were invited from abroad to train Russians. At the same time, he was not a supporter of blind admiration for foreign experience, but called for a critical approach to it, based on the interests of his country.

Ordin-Nashchokin’s outstanding diplomatic activity was aimed primarily at creating conditions for the development of foreign trade through the Baltic Sea. At the same time, he attached great importance to the development of foreign trade with eastern countries - Khiva, Bukhara, India. To develop trade, Ordin-Nashchokin considered it necessary to create a Russian merchant fleet. By decree of the tsar, he was put in charge of the “ship business”. He is credited with organizing the first post offices in Russia (1669).

Being a supporter of the Orthodox monarchy, Ordin-Nashchokin sought to strengthen the nobility, but, having revealed the objectively pressing needs for the economic development of the country, he thus actually became a spokesman for the interests of the merchants. He considered the merchants and nobility to be the support of the monarchy. In the tsar, Ordin-Nashchokin saw a defender of national interests. When carrying out economic reforms and transformations in the country, Ordin-Nashchokin attached great importance to the state, recognizing its right to intervene in the economic life of the country, regulate economic management, patronize and encourage trade monopolies and entrepreneurial activity.

Ordin-Nashchokin was interested in issues of the monetary balance in the country. He proposed a number of measures to retain precious metals in the country. The Merchant Unions he proposed were an attempt to organize credit and were the prototype of a bank in Russia. The streamlining of monetary circulation was only part of Ordin-Nashchokin’s economic program, which as a whole expressed a new period of Russian history, provided for the strengthening of trading capital and the creation of conditions for the development of domestic industry.

T. Semenkova

Materials from the site Great Encyclopedia of the Russian People were used.

Ordin-Nashchokin Afanasy Lavrentievich (approx., Opochka - 1680, Pskov) - state. and military leader. Genus. in the family of a landowner. In his father's house he received a comprehensive education and stood out noticeably among the provincial nobles. In 1622 he began “regimental service” in Pskov, becoming close to the Pskov governors and establishing contacts with Moscow. yard In the 40s was involved in the diplomatic service. In 1642 he was entrusted with carrying out border delimitation with Sweden. Showing his gift as a diplomat, Ordin-Nashchokin was sent to Moldova in the same year to receive comprehensive information about foreign policy plans Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and Turkey and not only eliminated the threat of war for Russia, but also strengthened Russian-Moldavian ties. During the Russian-Swedish war of 1656-1658, he was appointed governor and became the de facto ruler of Livonia, concluding the Truce of Valiesar in 1658, which allowed Russia to maintain its conquests in Livonia for 3 years. He was a supporter of concluding peace with the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and continuing the war with Sweden for the annexation of the Baltic Sea coast, but did not receive the support of the tsar Alexey Mikhailovich . He fought for recognition by the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth of the fact of the reunification of Ukraine with Russia. In 1667 he concluded the Andrusovo Truce Treaty, which put a limit to the expansion of the Polish gentry in the east and recognized the reunification of Left Bank Ukraine with Russia. For this great diplomatic success, Ordina-Nashchokina was granted a boyar status and appointed head of the Ambassadorial Prikaz. He consistently pursued a policy of patronage of domestic trade and supervised the drafting of the New Trade Charter of 1667, which regulated the activities of foreign merchants to ensure the trade interests of Russia. Under Ordin-Nashchokin, ties were established with the countries of Central Asia, China , India. Ordin-Nashchokin considered it necessary to replace the noble cavalry with “dacha” people and insisted on organizing regiments of regular infantry. He took a direct part in the creation of the first flotilla in Russia in the village. Dedinovo on the river Oke in 1667-1669. He also owns the authorship of the first Russian. ship charter. The desire for independence in diplomatic activities led Ordin-Nashchokin to conflict with the tsar and resignation in 1671. In 1672 he became a monk. Ordin-Nashchokin’s attempt to return to political activity, his appeals to the tsar were fruitless. Ordin-Nashchokin was one of the figures whose efforts prepared Peter’s reforms of the 18th century.

Book materials used: Shikman A.P. Figures of Russian history. Biographical reference book. Moscow, 1997

Ordin-Nashchokin Afanasy Lavrentievich - diplomat, boyar, governor. He directed foreign policy in 1667-1671, Ambassadorial and other orders. He signed a treaty of alliance with Courland (1656), the Treaty of Valiesar (1658), and concluded the Truce of Andrusovo with the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (1667). In 1671 he retired. In 1672 he became a monk. Ordin-Nashchokin was presumably born in 1605 into a nobleman’s family in the Pskov suburb of Opochka. Curiosity and a thirst for learning were characteristic of him from an early age; It was then that the love of reading began. A local priest taught him to read and write, a serving Pole taught him Latin and Polish. When Afanasy was 15 years old, his father took him to Pskov and enrolled him in the regiment for the sovereign's service. Educated, well-read, fluent in several languages, courteous Ordin-Nashchokin made a career thanks to his own talent and hard work. In the early 1640s, the Ordin-Nashchokin family moved to Moscow. The young nobleman was received in the house of the influential boyar F.I. Sheremetev.

In 1642, he was sent to the Swedish border “to clear the lands captured by the Russian Swedes and hay fields along the Meusitz and Pizhva rivers.” The Border Commission was able to return the disputed lands to Russia. At the same time, Ordin-Nashchokin approached the matter very thoroughly: he interviewed local residents, carefully read the interrogations of the “search people,” used scribe and census books, etc. By this time, Russian-Turkish, and therefore Russian-Crimean relations had worsened. It was important for Moscow to know whether there were Polish-Turkish agreements on joint actions against Russia. Ordin-Nashchokin was entrusted with this task. On October 24, 1642, he left Moscow with three assistants for the capital of Moldavia, Iasi. The Moldavian ruler Vasile Lupu cordially received the envoy of the Russian Tsar, thanked him for the gifts and promised all kinds of help. The Moscow diplomat was assigned a residence, food, and national clothes were sent. Ordin-Nashchokin collected information about the intentions of the Polish and Turkish governments and their military preparations, and also monitored events on the border. The actions of Polish residents in Bakhchisaray and Istanbul did not escape his attention. Through trusted persons, Ordin-Nashchokin knew, for example, what was discussed at the Polish Sejm in June 1642, about the contradictions within the Polish-Lithuanian government on the issue of relations with Russia. He carried out tireless observation of the actions of the Crimean khans and reported to Moscow that their ambassadors traveling from the tsar were killed by the Lithuanians, that they themselves were preparing their armies for an attack on Russia. Ordin-Nashchokin’s mission was also significant for greater rapprochement between Moldova and Russia. Based on the results of Ordin-Nashchokin’s observations and at his suggestion, in the spring of 1643 an embassy headed by I.D. was sent to Istanbul. Miloslavsky, which made it possible to conclude a peace treaty between Russia and Turkey. The agreement removed the threat from the southern direction, preventing military actions by the Crimeans against Russia.

In 1644, Ordin-Nashchokin was tasked with studying the situation on the western borders and the mood in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, in particular, checking rumors about an allegedly impending Polish-Danish invasion of Russia. Ordin found out that internal unrest in Poland and Lithuania would not allow Vladislav IV to settle border scores with Russia. And Denmark, which was fighting with Sweden, according to the diplomat, did not intend to quarrel with Russia. After the death of Mikhail Fedorovich in 1645, the throne was taken by his son Alexei. B.I. came to power. Morozov, the Tsar's brother-in-law, who replaced F.I. Sheremetev, who patronized Ordin-Nashchokin. The latter, left out of work, left for his Pskov estate. There he was caught in the rebellion of 1650, the cause of which was speculation in grain. Afanasy Lavrentievich proposed to the government a plan to suppress the rebellion, which subsequently allowed him to return to service. Ordin-Nashchokin was twice included in the border boundary commissions. In the spring of 1651, he went “to the Meusitz River between the Pskov district and the Livonian lands.”

In the mid-1650s, Ordin-Nashchokin became the voivode of Druya, a small town in the Polotsk voivodeship, directly adjacent to the Swedish possessions in the Baltic states. Negotiations between the governor and the enemy ended with the withdrawal of Swedish troops from the Druya area. He also negotiated with the residents of Riga about transferring to Russian citizenship. He organized reconnaissance, outlined the paths for the advancement of Russian troops, and convinced the residents of Lithuania of the need for a joint fight against the Swedes.

In the summer of 1656, in Mitau, Ordin-Nashchokin obtained the consent of Duke Jacob to help Russia, and on September 9, Russia signed a treaty of friendship and alliance with Courland. Afanasy Lavrentievich corresponded with the Courland ruler, the French agent in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and the Polish colonel. Received the Austrian ambassador Augustin Mayerberg, who was heading to Moscow. He showed concern for the revitalization of trade relations with German cities... Noting the successes of Ordin-Nashchokin, Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich appointed him governor of Koknese, subordinating the entire conquered part of Livonia to him. All Baltic cities occupied by Russian troops were transferred to the voivode's jurisdiction. Ordin-Nashchokin sought to establish good relations towards Russia among Latvians. He returned unjustly seized property to the population, preserved city self-government on the model of Magdeburg law, and in every possible way supported the townspeople, mainly merchants and artisans. And yet, Ordin-Nashchokin devoted most of his time to diplomatic affairs, developing his own foreign policy program. He carried it out with great tenacity and consistency, often entering into conflicts with Tsar Alexei himself. Afanasy Lavrentievich believed that the Moscow state needed “marinas” in the Baltic. To achieve this goal, he sought to create a coalition against Sweden and take Livonia from it. Therefore, he worked for peace with Turkey and Crimea, insisted on “making peace with Poland in moderation” (on moderate terms). Ordin-Nashchokin even dreamed of an alliance with the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, of “the glory that would cover the Slavic peoples if they all united under the leadership of Russia and Poland.” However, the foreign policy program of the “Russian Richelieu,” as the Swedes called him, did not meet with understanding from the tsar, despite the great trust and favor that he constantly placed in his minister. In April 1658, the tsar granted Ordin-Nashchokin the title of Duma nobleman. The royal letter noted: “You take care of our affairs with courage and bravery and are kind to the military people, but you don’t let thieves down and stand with our people with a brave heart against the Swedish king of glorious cities.”

At the end of 1658, the Duma nobleman, the Livonian governor Ordin-Nashchokin (being a member of the Russian embassy) was authorized by the tsar to conduct secret negotiations with the Swedes: “Take all possible measures so that the Swedes speak in our direction in Kantsy (Nienschanz) and near Rugodiv (Narva) ship piers and from those piers for travel to Korela on the Neva River the city of Oreshek, and on the Dvina River the city of Kukuinos, which is now Tsarevichev-Dmitriev, and other places that are decent.” It is noteworthy that Ordin was supposed to report on the progress of the negotiations to the Order of Secret Affairs. The ambassadorial congress began in November near Narva in the village of Valiesare. The Emperor was in a hurry to conclude the agreement, sending more and more instructions. In accordance with them, Russian ambassadors demanded the concession of the conquered Livonian cities, Korel and Izhora lands. The Swedes sought to return to the terms of the Stolbovo Treaty. The truce signed on December 20, 1658 in Valiesar (for a period of 3 years), which actually provided Russia with access to the Baltic Sea, was a major success of Russian diplomacy. Russia retained the territories it occupied (until May 21, 1658) in the Eastern Baltic. Free trade was also restored between both countries, travel, freedom of religion, etc. were guaranteed. Since both sides were at war with Poland, they mutually decided not to use this circumstance. The Swedes agreed with the honorary title of the Russian Tsar. And most importantly: “There will be no war and fervor on both sides, but peace and quiet.” However, after the death of King Charles X, Sweden abandoned the idea of “eternal peace” with Russia and even made peace with Poland in 1660. Russia once again faced the possibility of fighting a war on two fronts. Under these conditions, Moscow insisted on making peace with the Swedes as quickly as possible (getting one or two cities in Livonia, even paying monetary compensation) in order to turn all attention to the south. In this situation, Ordin-Nashchokin, in letters to the tsar, asks to be released from participation in negotiations with the Swedes. On June 21 in Kardis, boyar Prince I.S. Prozorovsky signed a peace agreement: Russia ceded to Sweden everything it had won in Livonia. At the same time, freedom of trade for Russian merchants and the liquidation of their pre-war debts were proclaimed. Ordin-Nashchokin’s participation in the Russian-Polish negotiations of the early 1660s, which became an important stage in the preparation of the Andrusovo Agreement, was exceptionally active. Realizing how difficult it would be to achieve reconciliation with the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, he solved this problem gradually. In March - April an exchange of prisoners took place, and in May an agreement was reached on the security of the ambassadors. But in June, a complete incompatibility of the positions of the parties on issues of borders, prisoners, and indemnity was revealed. Great restraint was required from the Russian great and plenipotentiary ambassador so as not to interrupt the negotiations.

The period from September to November 1666 is characterized by the strongest diplomatic attacks of the Poles, who began to seek the return of all of Lithuania, Belarus and Ukraine. But the head of the Russian delegation firmly stated that “the tsar will not make a concession to Ukraine.” Polish commissars threatened to continue the war. In a report to Moscow, Ordin-Nashchokin advised the Tsar to accept Polish conditions. In the last days of December, on behalf of the Tsar, Dinaburg was ceded to the Poles, but the ambassadors insisted on recognizing Kyiv, Zaporozhye and the entire Left Bank Ukraine as Russia. By the end of the year, the foreign policy position of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth had changed, and Polish representatives became more compliant. Already being a okolnichy, Ordin-Nashchokin soon took an active part in the renewed Russian-Polish negotiations. His restraint, composure, and diplomatic wisdom largely predetermined the signing of the most important agreement on January 30 (February 9), 1667 - the Peace of Andrusovo, which summed up the long Russian-Polish war. A truce was established for 13.5 years. Other important issues of bilateral relations were also resolved, in particular, joint actions against Crimean-Ottoman attacks were envisaged. On the initiative of Ordin-Nashchokin, Russian diplomats were sent to many countries (England, Brandenburg, Holland, Denmark, the Empire, Spain, Persia, Turkey, France, Sweden and Crimea) with “declaratory letters” about the conclusion of the Andrusovo truce, an offer of friendship, cooperation and trade. “The glory of the thirty-year truce that thundered in Europe, which all Christian powers desired,” wrote a contemporary of the diplomat, “will erect the noblest monument to Nashchokin in the hearts of his descendants.” The negotiations preparing the Andrusovo Peace took place in several rounds. And Ordin’s return to Moscow during one of the breaks (1664) coincided with the trial of Patriarch Nikon and his supporter, boyar N.I. Zyuzin, whom Ordin treated with sympathy. This cast a shadow on the Duma nobleman, although his complicity with Nikon was not proven. Nevertheless, Afanasy Lavrentievich had to ask the Tsar for forgiveness. Only the trust of Alexei Mikhailovich, as well as the selflessness and honesty of Ordin-Nashchokin himself, saved him from dire consequences: he was only removed to Pskov by the governor. But even in this position, Ordin remained a diplomat. He negotiated and corresponded with Lithuanian and Polish magnates, and thought about the delimitation of lands bordering Sweden. And to advance the cause of peace with the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, he tried to involve the rulers of Austria and Brandenburg, Denmark and Courland in mediation. Being an educated man, Ordin tried to give his son a good education. Warrior Afanasyevich “was known as an intelligent, efficient young man,” even sometimes replacing his father in Koknes (Tsarevich-Dmitriev city). But “passion for foreigners, dislike for his own” led him to flee abroad. True, in 1665 he returned from abroad and was allowed to live in his father’s village. However, this did not harm Ordin-Nashchokin’s career.

In February 1667, Ordin-Nashchokin was awarded the title of close boyar and butler and was soon appointed to the Ambassadorial Prikaz with the rank of “Royal and State Ambassadorial Affairs of the Boyar.” In the summer of the same year, the head of the Ambassadorial Prikaz also developed a sample of a new state seal, after approval of which he received the title “Royal Great Seals and State Great Ambassadorial Affairs Guardian.” Then he was entrusted with the Smolensk rank, the Little Russian order, the Novgorod, Galician and Vladimir cheties and some other orders, as a result of which he concentrated in his hands not only foreign policy, but also many domestic departments, becoming the de facto head of government. Ordina-Nashchokin paid great attention to expanding and strengthening Russia's international relations. It was he who tried to organize permanent diplomatic missions abroad. So, in July 1668, Vasily Tyapkin was sent to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth “to be a resident there forever.” Expansion of external relations required a certain awareness of events outside the country. For this purpose, on the initiative of the head of the order, postal communication was established with Vilna and Riga. He also introduced the practice of translating foreign newspapers and messenger letters, from which summary extracts were compiled - “Chimes”. These handwritten sheets became the forerunners of printed newspapers. During the four years of leading the Ambassadorial Prikaz (from February 1667 to February 1671), Ordin-Nashchokin streamlined the work of this institution. Thus, the staff was increased (in particular, the number of translators). He advocated for the professionalism of diplomatic personnel, because “it is necessary to direct our mental focus on state affairs to blameless and chosen people.” Ordin-Nashchokin highly valued the diplomatic service - “the trade”. In his eyes, the Ambassadorial Prikaz was the highest of all state institutions, “it is the eye of all great Russia, both for the state’s highest honor, together with health, and having providence on all sides and relentless care with the fear of God.” Ordin-Nashchokin was well prepared for the diplomatic service: he knew how to write “adjunctive”, knew mathematics, Latin and German, and was knowledgeable in foreign practices; They said about him that he “knows German business and knows German customs.” Not being an unconditional supporter of borrowing everything foreign, he believed that “a good person is not ashamed to learn from the outside, even from his enemies.” For all his dexterity, Ordin-Nashchokin possessed one diplomatic quality that many of his rivals did not have - honesty. He was cunning for a long time until he concluded an agreement, but, having concluded, he considered it a sin to break it and categorically refused to carry out the tsar’s instructions that contradicted this. He was distinguished by constant zeal in his work. However, he lacked flexibility and pliability in relation to court circles. He was proactive, resourceful, and was not afraid to defend his opinion before the king, in which he sometimes went beyond the limits acceptable at that time. So, in 1669, in response to an order to return to Moscow, the ambassador burst out with complaints and requests for resignation: “I was ordered to protect state affairs... I don’t know why I dragged myself from the embassy camp to Moscow?.. Should I wait for the ambassadors, or Is it time to go to Moscow, or should I really be relieved of embassy duties?” I was offended that they did not send the necessary papers; they called me to Moscow without explaining the reasons. So, Ordin-Nashchokin was in an aura of glory and enjoyed the unlimited trust of the tsar. But the tsar began to be irritated by too independent actions and independent decisions, as well as Ordin-Nashchokin’s constant complaints about the lack of recognition of his merits. The head of the Ambassadorial Prikaz had to give explanations. Over time, it became clear that his activities as the head of the Little Russian Order were not successful, and Ordin-Nashchokin was removed from this work.

In the spring of 1671, the title of “guardian” was deprived. In December, the tsar accepted the resignation of Ordin-Nashchokin and “clearly freed him from all worldly vanities.” At the beginning of 1672, Afanasy Lavrentievich left Moscow, taking away a large personal archive, ambassadorial books, and royal letters, returned to the capital after his death. In the Krypetsky monastery, 60 kilometers from Pskov, he took monastic vows, becoming monk Anthony. A few years later, in 1676-1678, the monk Anthony sent Tsar Fyodor Alekseevich two autobiographical notes and a petition outlining his foreign policy views. Despite Anthony's return to Moscow, his ideas were not in demand. It was reflected, in particular, that, having cut himself off from diplomatic life, the monk did not take into account the real situation, remaining in his previous positions. At the end of 1679 he returned to Pskov, and a year later he died in the Krypetsky Monastery. Ordin-Nashchokin was a diplomat of the first magnitude - “the most cunning fox,” in the words of foreigners who suffered from his art. “He was a master of original and unexpected political constructions,” says the great Russian historian Klyuchevsky about him. “It was difficult to argue with him. Thoughtful and resourceful, he sometimes infuriated the foreign diplomats with whom he negotiated, and they blamed him for the difficulty to deal with him: he will not miss the slightest mistake, no inconsistency in diplomatic dialectics, he will now pry and confuse a careless or short-sighted enemy."

Reprinted from the site http://100top.ru/encyclopedia/

Literature:

Collection of state charters and agreements stored in the State Collegium of Foreign Affairs. Part 4. M., 1828;

Soloviev S.M. A.L. Ordin-Nashchokin // St. Petersburg Gazette. 1850. No. 70;

Klyuchevsky V.A. L. Ordin-Nashchokin. Moscow statesman of the 17th century // Scientific word. 1904. Book. 3;

It's him. Russian history course. Part 3. M., 1937;

Chistyakova E.V. Socio-economic views of A.L. Ordina-Nashchokin (XVII century)//Tr. Voronezh. state un-ta. 1950. T. 20;

History of Russian economic thought. T. 1. Part 1. M., 1955. Ch. 9;

Galaktionov I.V., Chistyakova E.V. Ordin-Nashchokin - Russian diplomat of the 17th century. M., 1961.

Galaktionov I.V. Early correspondence of A.L. Ordina-Nashchokina (1642–45). Saratov, 1968.

A. L. Ordin-Nashchokin

Afanasy Lavrentievich Ordin-Nashchokin was born around 1607 into a noble family in the provincial town of Opochka, a suburb of Pskov. When Afanasy was 15 years old, his father took him to Pskov and enrolled him in the regiment for the sovereign's service. In the early 30s. Afanasy Lavrentievich got married and finally moved from Opochka to Pskov. Thanks to his remarkable natural talents, he quickly mastered foreign languages, mathematics and mechanics, and was distinguished by great erudition not only among the provincial service people, but also among the metropolitan nobles. He spoke easily to the Poles in Polish, and to the Lithuanians in their native language. He could also speak German, having learned this language from a visiting foreigner in Opochka.

In the early 1640s. The Nashchokin family moved to Moscow. The energetic provincial young nobleman was received in the house of the boyar F.I. Sheremetev and was soon introduced to the leading figures of the Moscow administrative administration. In 1642, Nashchokin took part in negotiations with Swedish commissioners on border disputes. The results were so successful that in the same year he was entrusted with a more important mission - the embassy to Moldova.

On October 24, 1642, Afanasy Lavrentievich went on his first trip abroad to the Moldavian city of Iasi. This city was not chosen by chance. Trade routes leading from East to West intersected here, in particular from the Ottoman Empire to Ukraine and Poland. According to a secret agreement between the Russian Tsar and the Moldavian ruler, it was agreed that Nashchokin would enter the service of Vasily Lupu and would carry out his personal instructions and orders. Service with the Moldavian ruler provided the Moscow envoy with reliable cover.

Ordin-Nashchokin began by studying the situation. First of all, Mikhail Fedorovich, the sovereign of Moscow, needed information about the plans of the Polish and Turkish governments and their military preparations against Russia. At that time, Greek monks and traveling Russian and Moldavian merchants had such intelligence information to some extent. Ordin-Nashchokin found the right approach to them, and frequent reports and observations about the situation on the Russian border began to go to Moscow. One of them, for example, set out in detail the content of anti-Russian speeches in the Sejm of Poland in 1642. Another spoke about the intention of the Crimean khans to make a campaign against Moscow, in the third - about the treachery of the Lithuanian princes and their conspiracy against the Moscow Tsar.

After the successful completion of the mission in Moldova, Afanasy Lavrentievich is entrusted with a new responsible task. There is an urgent need to find out about the intentions of the Polish-Danish detachments grouped for an attack in the western border regions of Russia. Ordin-Nashchokin managed to establish contacts with the archimandrite of the Dukhov Monastery in Vilna, using his previous experience of “working” with church hierarchs. Through Archimandrite A.L. Ordin-Nashchokin learned that Denmark did not intend to quarrel with Russia, and Poland would not attack Russia alone. This time, Ordin-Nashchokin’s activities received the approval of Tsar Mikhail Fedorovich himself.

In 1645, the Moscow throne was occupied by the son of the deceased tsar, Alexei. Reshuffles began in the government. B.I. Morozov, the royal brother-in-law, came to power, replacing F.I. Sheremetev, who patronized the Ordina. Finding himself out of work, Afanasy Lavrentievich leaves for his Pskov estate. There he was caught in the rebellion of 1650, the cause of which was speculation in grain. The plan to suppress the riot proposed to the government by Nashchokin served as the springboard from which he continued his career.

In 1652 and 1654 A. L. Ordin-Nashchokin is again included in the border boundary commissions, where he acts very successfully. At the end of 1654, Ordin-Nashchokin became the voivode of Druya, a small town in the Polotsk voivodeship, directly adjacent to the Swedish possessions in the Baltic states. An important stage in the biography of Afanasy Lavrentievich was his participation in the wars against the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and Sweden. Ordin-Nashchokin especially distinguished himself as a diplomat during the Russian-Swedish war of 1656–1658. After the capture of the town of Koknese (in Lithuania) by Russian troops, he was appointed governor there. All cities occupied by Russian troops in Livonia came under the jurisdiction of Afanasy Lavrentievich. The policy pursued by Ordin-Nashchokin in the Baltic states had a deep economic meaning and subtle political calculation. He sought to establish a good attitude towards Russia among the local population. A talented administrator, Ordin-Nashchokin returned unjustly seized property to residents, preserved city government, the rights and freedoms of citizens in the form of Magdeburg law, and supported artisans and merchants.

At the same time, Afanasy Lavrentievich constantly took care of the strategic strengthening of the area under his jurisdiction and increasing the combat effectiveness of the troops. He carefully studied the theater of possible military operations in the Baltic states and regularly reported his observations to the tsar. In secret messages to Moscow, Afanasy Lavrentievich indicated the number of Swedish armed forces, gave a detailed description of the state of roads and military fortifications, and recommended the most convenient routes for the movement of Russian troops. As a reasonable politician and perspicacious diplomat, Nashchokin advised the tsar to more widely apply the practice of hiring Latvian soldiers for paid military service in the Russian army. In his opinion, this would contribute to the growth of Russophile sentiments among the Baltic population.

But still, Afanasy Lavrentievich devoted most of his time to developing his own foreign policy program. He rightly believed that it was impossible to simultaneously wage war with the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth for Ukraine and Sweden for Livonia. Ordin-Nashchokin spoke out for peaceful relations with Poland and was even ready to sacrifice Ukraine for the sake of an alliance with the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth against Sweden. An ardent supporter of the strengthening of Russia in the Baltic, Nashchokin achieved the official transfer of Courland under the patronage of Russia. In order to counter the Swedish fleet, he took measures to begin the construction of the Russian fleet on the Western Dvina. However, Afanasy Lavrentievich’s plans did not receive support in Moscow. In the foreign policy of the Russian state, supporters of resuming the war with Poland won.

War of 1658–1667 was actually a continuation of the previous war for Ukraine, which began in 1654. After the death of Bogdan (Zinovy) Mikhailovich Khmelnitsky on July 27, 1657 from a cerebral hemorrhage, Moscow decided that Ukraine had already finally merged with Russia. This confidence in resolving the Ukrainian issue led to a desire to limit the rights of Ukraine. Moscow tried to put Ukraine's foreign policy under its control, take tax collection into its own hands, and place Russian governors and garrisons not only in Kyiv, but also in other cities. This policy of Russia contributed to the fact that the new hetman of Ukraine I. E. Vygovsky decided to return Ukraine to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

Unlike Bohdan Khmelnytsky, who saw the possibility of preserving Ukrainian statehood in a confederation with Russia, Ivan Vygovsky intended to preserve this statehood as part of a weaker and decentralized Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. In 1657, Vyhovsky concluded an alliance treaty with the Crimean Khan, and on September 6, 1658, in the city of Gadyachi, the hetman signed an agreement on the return of Ukraine to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The Polish Sejm did not ratify this treaty and, regardless of reality, demanded the return in Ukraine of those orders that existed before 1648. In Ukraine, the Cossacks of the Poltava and Mirgorod regiments, as well as the ataman of the Zaporozhye Sich, Ya. F. Barabash, rebelled against Vygovsky, who accused hetman in treason.

In January 1658, the Russian-Polish war resumed. Vygovsky tried to keep the Gadyach Treaty a secret from Moscow. The hetman's open armed action against Russia began in August 1658. I. E. Vygovsky's transition to the side of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth meant for Russia the resumption of the war with Poland and Crimea, in the context of the ongoing war with Sweden.

In April 1658, the tsar appointed Ordin-Nashchokin to the Duma clerk and instructed him to urgently begin secret negotiations on peace with Sweden. As a result of negotiations, a truce was signed in December 1658 in the village of Valiesari (Vallisaari). The armistice period for Russia was determined to be 3 years, for Sweden - 20 years. In practice, this meant that Sweden could violate the armistice agreement after 3 years on a completely legal basis. Russia did not have the right to start a war with Sweden for 20 years. The inequality of rights between the parties reflected the real balance of power in the Baltic states. But according to the agreement, Russia maintained its conquests in Livonia until the end of the established years of truce, which was considered by Russian diplomacy as a major success.

In 1661, at the Kardis (Kärdi) manor, an “eternal peace” was signed between Russia and Sweden. The first Russian delegation at the negotiations was headed by Ordin-Nashchokin. Afanasy Lavrentievich was distinguished not only by the art of soft and cunning maneuver, but also by his “bulldog” grip. From the very beginning of the negotiations, he took a tough stance towards the territorial demands of Swedish diplomats. Then the Swedes complained to the tsar that the reason for the delay in peace negotiations was solely the uncompromising position of Ordin-Nashchokin. On January 10, 1661, Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich ordered Nashchokin to hand over all matters to the new delegation led by Prince I. S. Prozorovsky, who completely lost the diplomatic duel with the Swedes. The agreement was signed on June 21, 1661. Prozorovsky ceded all those territories in Livonia that Ordin-Nashchokin had defended in Valiesari in much worse circumstances. Thus, Nashchokin’s diplomatic plans were destroyed. But, despite this, he continued to persistently try to convince the tsar of the need to make peace with Poland, proving that the possession of Livonia was more profitable for Russia than the annexation of Ukraine.